Theme: Aves, Nomenclature, Factual, Birding.

Reading Time: 10 minutes.

Please subscribe to receive my latest posts about nature & science straight to your email inbox. 🌏👩🏽🔬😀

I ask you, what bird is this?

Source: http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20160803-the-strange-reason-magpie-larks-dance-when-nobody-is-looking

If you answered, “that’s the piping shrike!”, well, I’m sorry to say my friend, but you are incorrect!

I will present the evidence and explain the confusion below.

Confusing one thing for another is in no way uncommon. Like mistaking a massive hare for a rabbit, fearing poisonous snakes that are actually venomous, or even naming many sea creatures “fish” such as jellyfish, starfish or cuttlefish, all of which are not really fish at all.

But if an animal is on your state flag, is it acceptable not to know it when you see it?

I refer to the Australian magpie (piping shrike) which is on my state’s flag, the flag belonging to the state of South Australia. If such an animal appears on your state flag you should know what that animal is… shouldn’t you?

Well, unfortunately, that is not the case here.

A few months back I was at work one night and was visited by a friend who pops in now and then to say hello. He is usually quite stealth, and no one really notices when he’s around. He just quietly drops in to have a nosey when the time is right.

Now, I admit, he doesn’t come in just to see me, I believe for the most part he is just checking to see if any birdseed bags have been split open on the back dock with the hope of getting a belly full of free food.

Yes, my friend eats birdseed, and he loves it.

Those with a scientific background or an interest in birds may know him more specifically as Grallina cyanoleuca, and I know it’s a “him” as he has thick white eyebrows (a distinguishing male phenotype). My pied little friend has become quite the regular, and I am always happy to see him pop in looking healthy and happy, even though he clearly only visits me for his own benefit.

One night when at work, my white-eyebrowed and pied friend dropped in to say hello. As I had been practising the scientific names of birds at the time, I proudly announced to my comrade “Grallina cyanoleuca” as I pointed to our petite visitor.

“What does that mean?” my colleague replied.

I quickly explained that I was practising the scientific names for our local birds and the words I had just announced were the scientific names (genus and species) given to that bird, the magpie-lark.

He was quick to laugh at me, “that’s not a magpie-lark mate, that’s the piping shrike” he said smugly.

Well, I was just learning, so unconfident at the time I dare not argue my point and thought maybe he knew more than I did. So, I carried the doubt with me for the rest of my shift.

Once home I was straight to my computer to do some research and find out where I had gone wrong. I was delighted to find that I was not mistaken and in fact, the bird friend who was visiting me earlier at my work was the magpie-lark (Grallina cyanoleuca), not a piping shrike.

That was not to be the last time I was filled with doubt surrounding this issue.

A few months later, as little as 1-2 months ago, while walking my dog Bruce around our neighbourhood, I was lucky enough to notice what I suspected was a magpie lark in a nest. The pied bird had built a mud nest which sat upon the vertical branch of a bottlebrush tree. This bird was sitting stationary and only moved away for a moment when it noticed me and my pooch standing below looking up and admiring. But it was quick to return once I strayed a few meters further down the street and took up a different position to see what it would do. I returned and again it flew away. A precautionary method obviously as once I strayed afar again it immediately returned to its nest.

From the behaviour observed, and the quietness of the nest when the bird was not within it, I correctly assumed it was incubating a clutch of eggs and for the next week or so when I walked my dog under the same bottlebrush tree, I observed the same behaviour.

Until 1 day when I could hear chirping from within the nest which must have been hatchlings. I was delighted to observe this occurrence just on the verge of spring and was sure to keep an eye on the situation for the next few weeks.

Over the next 2-3 weeks, I observed mother and father swapping on the nest, taking it in turns to gather and return with food, and the increasing size of each of the three chicks of the brood. This carried on much to my pleasure until one day I returned, and the nest was empty, with no adults, no chicks and no evidence of any foul play. So, I can only assume a happy ending to that story.

However, if I rewind the clock a week or so to a bright and sunny day when I was standing at a distance and observing this soon-to-be bird family’s behaviour, I recall a moment that caught me off guard.

“What are you looking at?” a voice would say from over the road.

I looked over to see an older woman who must have been in her 60’s or 70’s, who had stopped her mobility scooter on the footpath directly across the road from where I stood so obviously intrigued. She was staring at me staring at something within the tree.

“What have you found love?” she repeated as she gently stroked a small dog which sat upon her lap.

“A magpie-lark feeding her brood” I replied confidently, enjoying the opportunity to show off my newfound expertise.

“Magpie-lark?” she seemed puzzled.

“Yes, a magpie-lark, you know, it looks like a magpie, only smaller and more petite” I responded.

“Oh, you mean a piping shrike” she replied as she began on her way again.

“Pretty common this time of year” she announced as she drove off down the street.

Once again, I was left questioning myself, although this time I was slightly more confident I was correct.

I headed home again and immediately researched the magpie-lark and piping shrike, and I was right, only this time I was slightly happier as I was growing ever more confident in my identification of the bird.

The magpie-lark, also known as the peewee or peewit (after the sound of its distinctive calls), mudlark, murray magpie, and ever more commonly and mistakenly as the “piping shrike”, is a passerine bird which is native to Australia, Timor and southern New Guinea. Importantly I reiterate, the magpie-lark (Grallina cyanoleuca) does not appear on the South Australian flag and is not a “piping shrike”.

In fact, to add more confusion to the matter, the magpie-lark (Grallina cyanoleuca) is not a magpie, or a lark, and is actually more closely related to Monarchs, Fantails and Drongos. However, In 1977, the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union (RAOU) settled on Australian magpie-lark as the official name, noting that the names magpie lark and, less commonly, mudlark were used in guidebooks at the time.

It is easy enough to distinguish between a mature male and a mature female magpie-lark as the adult male has a white eyebrow and a black face while the adult female has an all-white face with no white eyebrow.(1)

Image: A male magpie-lark with the clearly visible white eyebrow.

Source: http://www.birdlife.org.au/bird-profile/magpie-lark

Image: A female magpie-lark with no white eyebrow and a white face.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Magpie_Lark_female.jpg

However, while distinguishing male magpie-larks from females seems relatively easy, distinguishing the magpie-lark itself from the piping shrike (Australian magpie) seems to be an area of much confusion amongst everyday Australians and more specifically my fellow South Australians.

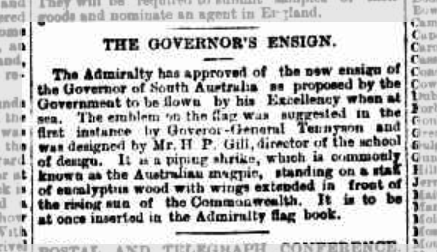

This erroneous way is largely in part due to the nickname “piping shrike” not technically used to identify any bird, and due to this a lot of confusion has resulted over what bird the term represents. While some think it refers to the magpie-lark (Grallina cyanoleuca), the actual original reports specify that it is based on the Australian magpie.(2)

Image: THE GOVERNOR’S ENSIGN. – The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954) – 16 Mar 1903.

Article reads;

“THE GOVERNOR’S ENSIGN.

The Admiralty has approved of the new ensign of

the Governor of South Australia as proposed by the

Government to be flown by his Excellency when at

sea. The emblem on the flag was suggested in the

first instance by Governor-General Tennyson and

was designed by Mr. H. P. Gill, director of the school

of design. It is a piping shrike, which is commonly

known as the Australian magpie, Standing on a staff

of eucalyptus wood with wings extended in front of

the rising sun of the Commonwealth. It is to be

at once inserted in the Admiralty flag book.”

Government sources also support this claim and state;

“The State Badge of a piping shrike (also known as a White Backed Magpie), was notified by a proclamation gazetted on 14 January 1904. The original drawing of the piping shrike was done in 1904 by Robert Craig of the School of Arts. A later drawing was done in 1910 by Harry P Gill, who was the Principal of the School of Arts”.(3)

Now, let me show you, this is the South Australian flag (below). It features a white-backed Australian magpie (piping shrike) perched on a staff of eucalyptus and facing the rising sun.

Image: The South Australian Flag.

Source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/flag-of-South-Australia

As you can see it has no white eyebrow and no white face, so it is not the magpie-lark, and you can tell we are viewing its back as the claws which grip the eucalyptus staff are facing the sun with the back claw visible and its 3 front-facing claws hidden. Therefore this can only be a white-backed magpie (piping shrike).

And this is a photo of the white-backed magpie (piping shrike).

Image: White-backed magpie (piping shrike).

Source: https://www.projectnoah.org/spottings/15841184

Below is the magpie-lark. Or the peewee, peewit, murray magpie or mudlark as it is called, and importantly, this is not a piping shrike.

Image: A male magpie-lark next to his nest and brood of two chicks.

Source: http://members.ozemail.com.au/~bajan/Magpie-larks/Magpie-lark%20or%20Peewee.htm

You can see why it is easily confused with the back of the piping shrike (Australian magpie) on the South Australian flag, as this bird in the image, the magpie-lark, looks very similar.

So, now you know, once and for all, the piping shrike is the large Australian magpie who is also featured on the South Australian flag, and the piping shrike is not the petite magpie-lark.

Next time you see someone call the smaller petite passerine bird the piping shrike you can tell them that the bird they refer to is the magpie-lark and the piping shrike is a term that refers to the much larger Australian magpie.

If they don’t believe you, refer them to this article.

Hope I helped clear that up for you.

Check out my future posts and articles and subscribe below and if you have any questions don’t hesitate to comment at the bottom of this page or on my Facebook feed and I’ll be sure to answer you straight away.

Thank you and enjoy,

W. A. Greenly.

W. A. Greenly’s upcoming articles include:

- How to Train an Environmentalist.

- The Mystery of the Australian Megafauna.

- Recycling Made Simple.

Literature cited:

- http://www.carterdigital.com.au, C. (2019). Magpie-lark | BirdLife Australia. Retrieved 21 November 2019, from http://www.birdlife.org.au/bird-profile/magpie-lark).

- THE GOVERNOR’S ENSIGN. – The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954) – 16 Mar 1903. (2019). Retrieved 21 November 2019, from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/14568342?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FS%2Ftitle%2F35%2F1903%2F03%2F16%2Fpage%2F1335271%2Farticle%2F14568342.

- Using the state insignia and emblems. (2019). Retrieved 21 November 2019, from https://www.dpc.sa.gov.au/responsibilities/state-protocols-acknowledgements/using-the-state-insignia-and-emblems.