Theme: Dingo, Nomenclature, Factual, Ecology.

Reading Time: 15 minutes.

Australia’s top predator is fighting for its identity, and its survival.

Are dingoes native wildlife or wild dogs? The answer matters more than you might think. As you’re about to learn, from shaping ecosystems to controlling invasive species, the dingo plays a critical role in Australia’s environmental balance. Yet, the debate rages on.

If you care about evidence-based conservation, ecological truth, and the survival of native species, you’re in the right place, because so do I.

Before reading on, please take a second and subscribe to get clear, grounded, and timely articles that cut through confusion and help you stay informed.

Above: An Australian dingo on the move, 10 km north of The Dingo Fence, South Australia.

(Source: Photograph taken by Jack Bilby, 03/04/2023).

I first became interested in dingoes while travelling from Adelaide to Perth via the Nullarbor in my mid-twenties. At first, it was the roadside signs I drove past stating 1080 baiting in this area which stirred my curiosity but after a bit more research it was the reports and the horrific stories of the 1080 (ten-eighty) baiting’s effects on dingoes (and the occasional traveller’s unlucky canine companion) that grasped my attention. Since then, it’s become apparent to me that the dingo debate is a long and ongoing one across all states and territories of Australia.

Throughout my time at university, the debates surrounding dingoes, their threats, and their ecological significance were always an engaging group discussion. I also regularly see the topic on the news, my Facebook feed and dingoes have even been the expert topic selected by a few contestants on ABC’s The Hard Quiz (which I watch regularly). It seems there’s no doubt about the dingo’s importance to the people of Australia, no matter what side of the dog fence you sit on (pun intended).

More recently, while working on remote properties in Western Australia I had the unfortunate experience of witnessing dingoes trapped in leg traps which were either set with incorrect amounts of strychnine, or with the strychnine in the wrong place meaning the trapped dingoes would have suffered the effects of dehydration for days before the relief of death had we not come across them. I witnessed this first-hand on several occasions and trust me, for anyone with half a conscience it’s a heartbreaking experience. However, what’s equally alarming is often what I see and hear on the topic of dingoes are common misconceptions or just plain myths. For this reason, I’ve taken the time to compile a list of common questions I hear and answered them with facts, not fiction, for both my understanding and yours. I hope this is a useful resource that sparks your interest or just answers some questions you may have. As always, I’d love to know your thoughts or personal experiences on the subject too, so please don’t hesitate to leave a comment at the end.

What’s the difference between a pure dingo and a wild dog?

Dingoes migrated to Australia at least three thousand years ago(1). Due to long-term geographical isolation (allopatric separation), dingoes are now considered genetically, phenotypically, ecologically and behaviourally distinct from other Canis species and are unique to Australia(2,3).

On the other hand, wild dogs are individuals from breeds of domesticated dog (the result of selective breeding by humans) that have strayed from, or been dumped by humans.

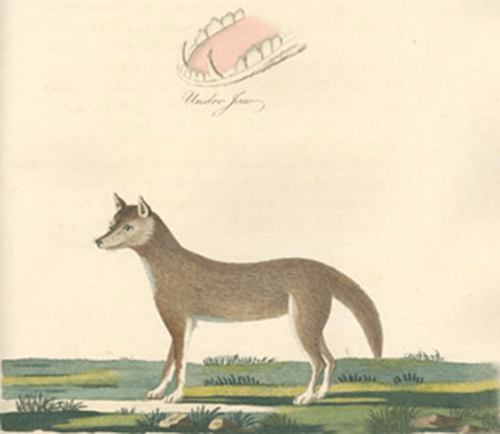

How do you identify a pure dingo?

A pure dingo is any dingo that is not hybridised with any wild, domestic or hybrid dog. A pure dingo is usually only identifiable by skull measurements and/or DNA sampling to determine their genetic makeup(4,5). Importantly, contrary to previous beliefs, pelage (fur colour/growth style) has proven to be an unreliable characteristic and should not be used to differentiate dingoes from wild dogs(6).

Above: ‘Dog of New South Wales’.

(Source: Mazell, P. and Phillip, A., 1789. Dog of New South Wales. The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay with an account of the establishment of the colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, J. Stockdale, London. Available from: http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/e00101.html#phillip-46 (accessed: 05 August 2024).

Are there any pure dingoes left?

While it is widely understood that hybridisation threatens the conservation of pure dingo lineage, it is certainly not true to say there aren’t any pure dingoes left.

A study conducted in 2021 sampled the DNA of 5,039 wild canids providing strong evidence that pure dingoes are not just extant (not extinct), but still dominate Australian ecosystems in comparison to wild dogs. Out of the 5,039 dogs sampled, only 31 feral dogs were detected and a further 27 individuals were found to be first-generation dingo x dog hybrids(7).

More recently, a study by Cairns et al. (2023)(29), which utilised more extensive DNA testing procedures (on 402 dingoes from a broad geographical range across Australia), ancestry modelling and biogeographic analyses allowed researchers to identify two key findings:

- At least four genetically distinct dingo populations (and one captive dingo population) exist in Australia.

- The presence of dog ancestry in wild dingoes is much less common than previously hypothesised in studies that used less extensive DNA testing procedures.

These studies along with others which have sampled dingo DNA, strongly reject both common misconceptions that dingoes are extinct in the wild and that feral dogs are abundant throughout Australia(7,29). In fact, the sheer rarity of hybrids witnessed in these studies adds support to claims dingoes rarely breed with domestic/wild dogs and in any rare case where they do, the resulting hybrids have little chance of survival in the wild(7,29).

What is the dingo’s scientific name?

Over many years of healthy, scientific debate on the subject of dingo taxonomy and nomenclature, the dingo has been called a variety of scientific names; Canis lupus dingo (classifying it as a subspecies of wolf), Canis familiaris (classifying it as a breed of domestic dog), and Canis dingo (classifying it as a unique species in the genus, Canis), as well as other combinations such as Canis familiaris dingo and Canis lupus familiaris(8). This debate is ongoing and is likely to continue as the answer appears different depending on which species concept (the method used for defining a species) is employed(9).

Above: The Warrigal (old dingo) and the Mundurra (hunter) stalking the bunderra (black wallaby)

(Source: https://www.dingoden.net/noble-spirit.html#:~:text=Indigenous%20Australians%20would%20often%20acquire,night%2C%20and%20were%20protected%20jealously).

Did Aboriginal Australians have dingoes as pets?

Yes. Historical sources and Indigenous oral traditions teach us that Aboriginal Australians caught and reared the pups of dingoes as pets(10). The evidence available shows that Aboriginal Australians formed close bonds with dingoes through an active socialisation process from an early age(10). These dingo-human relationships were maintained through time by the passing down of oral lessons teaching children about the dangers of wild and unfamiliar dingoes while also communicating the importance of treating the animals with respect(10). To this day the Australian dingo is not only an Australian icon, but also maintains its long-standing position in First Nation’s culture and daily life as a hunting companion, family member and protector(11).

Are dingoes important to Australian ecosystems?

Yes.

A large body of research now recognises that through direct predator/prey relationships and indirect processes known as trophic cascades, Australia’s apex predator, the dingo, plays a pivotal role in the management of Australia’s biodiversity and ecosystems(12,13,14,15,16).

Feral herbivores such as goats, pigs and rabbits and native mammals including kangaroos, wallabies and wombats as well as birds, lizards and in some places even fish (like on K’gari – Frazer Island) and water buffalo (in Northern Territory) are all the direct prey of dingoes(15). By hunting and reducing the numbers of these animals, the dingo has a direct effect on the populations and survival of such prey animals(13,14,15,16). At the same time, by regulating numbers of native and feral herbivorous animals, dingoes also have an indirect effect on the abundance and diversity of vegetation across Australia(13,14,15,16). In fact, the sheer presence of dingoes has been shown to ward off introduced mesopredators (mid-ranking predators) such as the red fox Vulpes vulpes, or the cat Felix catus(13,14,15,16). This means just by being present in the environment, dingoes directly reduce mesopredator numbers, thus indirectly increasing herbivore numbers and indirectly altering grazing affects on vegetation communities(13,14,15,16).

It is also evident that where dingo numbers have been lost or significantly reduced, cascading losses in various small to medium-sized native mammals, the explosion of herbivore populations resulting in the exhaustion of plant biomass, and the increase of predation rates on native species by red foxes, has increased(14). Studies show that across all scenarios, the predation and presence of dingoes aids the balance of ecosystems and the survival of Australian native plant and animal species(13,14,15,16).

Are dingo numbers declining and what threats do dingoes face?

Australia’s dingo populations are decreasing(17). These are the dingo’s most significant threats:

Habitat loss: Similar to many Australian species, habitat loss is a major and increasing threat to dingoes(18).

Hybridisation: The hybridisation of the pure dingo with wild, domestic and hybrid dogs is an increasing threat to Australia’s unique dingo lineage(18).

Pest status: Whether the dingo is a ‘pest’ or indeed a native species is the subject of much ongoing debate. This ‘pest’ status along with the labelling of dingoes as ‘Wild Dogs’ is responsible, and in most scenarios even provides a licence for, the mass destruction of dingoes by methods such as broad-scale baiting (ten-eighty), trapping and shooting(18).

Just like it did the Tasmanian Tiger, this destruction partnered with other pressing threats leaves Australia’s dingo vulnerable to extinction(17,18).

Above: A dingo scans the area.

(Source: https://pixabay.com/users/tahliastantonphotography-8583514/).

Are dingoes a protected species?

The Australian dingo is not a nationally protected species.

Despite once being listed as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN)(17) dingoes were removed after a review in 2019(19,20,21).

Within Australia, the dingoes’ status varies from state to state.

In New South Wales for example, the dingo is still the only Australian mammal not protected under the National Parks and Wildlife Act and is instead recognised as a wild dog under the Rural Lands Protection Act(22,23,24).

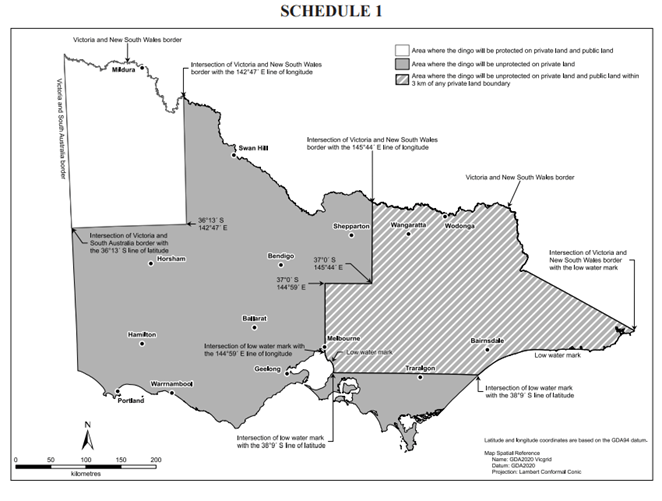

In Victoria in March of 2024, the Government enacted changes to the dingo unprotection order to protect an at-risk population of dingoes in the state’s north-west due to scientific information which identified the population as being at imminent risk of extinction(30). In north-west Victoria the genetically distinct and geographically isolated Big Desert dingoes (known as Wilkerr to the people of the Wotjobaluk Nations) are now protected on both public and private land meaning it is an offence to destroy or harm dingoes within this zone without authorisation(30,31).

Above: Map of Victoria showing the north-west zone where dingoes have full protection (white).

Source: Victorian Government Gazette, 14th March, 2024 – https://www.gazette.vic.gov.au/gazette/Gazettes2024/GG2024S123.pdf).

Elsewhere in Victoria (outside of the defined north-west zone), dingoes are still declared unprotected on private land across the state and on public land within 3 km of the boundaries of any private land in the east of the state(30). In these areas, it is reported that dingoes are being killed in ramped-up efforts to eradicate them for commercial purposes (to eliminate their risk to livestock)(25). As dingoes were removed from the IUCN Red List in 2019, there is also mounting pressure on the Victorian government from the livestock-industry-driven initiative, the National Wild Dog Action Plan, to review and remove the limited protections the dingoes have in the north-west region(20).

The sad reality is that throughout Australia the only true refuge for dingoes in their natural habitat is within National Parks and some designated Conservation land. However, in most cases baiting and other control methods are often permitted on the borders of these supposed safe-havens. Across Australia, the dingo is subject to a range of government-funded controls such as trapping (including inhumane leg trapping), aerial and ground baiting (with for example ten-eighty baits), and even by government-funded hunting bounties(22,24,25,26,27,28).

Above: An Australian dingo scans for the threatening Wedge Tailed Eagle, 10 km north of The Dingo Fence, South Australia.

(Source: Photograph taken by Jack Bilby, 03/04/2023).

W. A. Greenly’s take.

Throughout this article, I have (for the most part) kept my feelings and opinions on the matter silent to try and convey only unbiased, factual information. However, if I was asked to give it, I’d first point out that when it comes to the debate surrounding the control of dingoes in Australia, the answer seems to differ largely depending on which of the two main camps you sit in, or ask.

For those ecologically and culturally inclined, it seems evident that the dingo’s isolation of around 3,500 years has undoubtedly led to it being unique in many facets (genetically, phenotypically, ecologically and behaviourally) as well as its status as an apex predator in Australia and its effect on Australia’s biodiversity and ecosystems being well established and further understood every day. Alongside ecological importance, people in this camp also seem to understand that of First Nations people’s cultural and spiritual significance of, and connection to the animal.

On the contrary, there are those in the farming (and supporting bodies) camp. Now, I’ll be very careful here not to paint all people in this camp with the same brush as I know for a fact some very much support working with dingoes, not against them. However, for many with a commercial interest, it seems the non-protection and subsequent controlling of dingoes (to reduce the impacts on their livestock) is priority, despite the broader ecological effects. It also seems to me that the arguments of dingo or wild dog, and pest or native species, are used by parties within this camp as distractions, while the killing goes on. These debates live on despite the evidence that dingo x wild dog hybridisation is rare, and despite the lack of any evidence (certainly that I could find) of any roaming domestic dogs forming wild living, feral populations.

No matter which of the these two camps you sit in, and despite everything I’ve noted above, in my mind there’s only one question that needs answering: Is the dingo’s isolation of around 3,500 years, its resulting global uniqueness and its ecological importance to Australia enough to deem it worth protecting despite the effect on the industries we’ve established here?

For me, the answer is certainly yes.

The dingo, its place of maintaining a balance within Australia’s ecosystems, and its special position culturally and spiritually among Aboriginal Australians were all well and truly established before the arrival of Europeans to this magnificent continent. In my opinion, Australian’s have a duty to protect dingoes and in doing so, maintaining and providing longevity to Australia’s fragile ecosystems. There’s also no doubt in my mind we must respect the long-running relationship between dingoes and Aboriginal Australians.

It’s obvious to me that the longer the debates run, the higher the chance we will lose this incredible animal from Australia resulting in yet more damage to Australia’s unique and already decaying ecosystems. What truly matters should be the importance of dingoes to Australia’s ecosystems and that should be put above whether we humans define dingoes as unique species or wild dog, native animal or pest. More and more research points to the dingo being of conservation value throughout Australia, and it is clear that the removal of dingoes contributes to ecosystem collapse. Protecting Australia’s dingo will go a long way to protecting Australia’s already fragile systems.

So, what do you think?

I’d love to hear your opinion and about your experiences with dingoes. Please comment at the bottom of this page and I’ll be sure to respond.

Thanks for reading. This article’s a labour of love.

If you care about nature and want more people to see science-based stories like this, the answer is simple, just subscribe to my blog, and like or share this article. It helps more than you think, and it also means the world to me.

Thank you,

Mr. Greenly.

Enjoy science, nature and the worlds many marvelous critters just as much as I do? Be sure to check out my blog menu for more fascinating readings! See you there!

References:

- Balme, J., O’Connor, S. and Fallon, S., 2018. New dates on dingo bones from Madura Cave provide oldest firm evidence for arrival of the species in Australia. Scientific reports, 8(1), p.9933.

- Smith, B. ed., 2015. The dingo debate: origins, behaviour and conservation. CSIRO Publishing.

- Smith, B.P., Cairns, K.M., Adams, J.W., Newsome, T.M., Fillios, M., Deaux, E.C., Parr, W.C., Letnic, M., Van Eeden, L.M., Appleby, R.G. and Bradshaw, C.J., 2019. Taxonomic status of the Australian dingo: the case for Canis dingo Meyer, 1793. Zootaxa, 4564(1), pp.173-197.

- Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (2016) Wild dog fact sheet: Biology, ecology and behaviour. Available at: https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/66153/IPA-Wild-Dog-Fact-Sheet-Biology-Ecology-Behaviour.pdf.pdf (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Duffy, J. (2019) I’m a dingo: Don’t call me a dog!, Echidna Walkabout Tours. Available at: https://echidnawalkabout.com.au/dingo-not-a-dog/#:~:text=Dingoes%20have%20consistently%20broader%20heads,are%20all%20natural%20dingo%20colours (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Crowther, M.S., Fillios, M., Colman, N. and Letnic, M., 2014. An updated description of the Australian dingo (C anis dingo M eyer, 1793). Journal of Zoology, 293(3), pp.192-203.

- Cairns, Kylie M., Mathew S. Crowther, Bradley Nesbitt, and Mike Letnic. “The myth of wild dogs in Australia: are there any out there?.” Australian Mammalogy 44, no. 1 (2021): 67-75.

- Jackson, S.M., Fleming, P.J., Eldridge, M.D., Archer, M., Ingleby, S., Johnson, R.N. and Helgen, K.M., 2021. Taxonomy of the dingo: It’s an ancient dog. Australian Zoologist, 41(3), pp.347-357.

- Cairns, K.M., 2021. What is a dingo–origins, hybridisation and identity. Australian Zoologist, 41(3), pp.322-337.

- Brumm, A. and Koungoulos, L., 2022. The role of socialisation in the taming and management of wild dingoes by Australian aboriginal people. Animals, 12(17), p.2285.

- Cairns hosts First Nations Dingo Forum [online], (2024). Indigenous.gov.au. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.indigenous.gov.au/news-and-media/stories/cairns-hosts-first-nations-dingo-forum

- Dingoes [online], (2024). Wildlife. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.wildlife.vic.gov.au/our-wildlife/dingoes

- Dingo effects on ecosystem visible from space [online], (2021). UNSW Sites. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2021/02/dingo-effects-on-ecosystem-visible-from-space-

- Letnic, M., Ritchie, E.G. and Dickman, C.R., 2012. Top predators as biodiversity regulators: the dingo Canis lupus dingo as a case study. Biological Reviews, 87(2), pp.390-413.

- Dingoes [online], (date unknown). BushHeritageMVC. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.bushheritage.org.au/species/dingoes#:~:text=The%20bulk%20of%20their%20diet,known%20to%20hunt%20water%20buffalo!

- Dingoes [online], (date unknown). Environment | Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Queensland. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://environment.desi.qld.gov.au/wildlife/animals/living-with/dingoes

- Corbett, L.K. 2008. Canis lupus ssp. dingo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T41585A10484199. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41585A10484199.en

- Bush Heritage Australia (date unknown) Dingoes, BushHeritageMVC. Available at: https://www.bushheritage.org.au/species/dingoes#:~:text=Threats%20to%20Dingoes&text=The%20Dingo%20is%20persecuted%20on,Red%20List%20of%20Threatened%20Species (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- New drive to reinstate wild dog control in north-west Victoria – Sheep Central [online], (2024). Sheep Central. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.sheepcentral.com/new-drive-to-reinstate-wild-dog-control-in-north-west-victoria/#:~:text=As%20a%20result%20of%20their,conservation%20concern,%20the%20NWDAP%20said.

- Time to reinstate the dingo unprotection order in northwest Victoria – National Wild Dog Action Plan [online], (2024). National Wild Dog Action Plan – Wild Dog Management in Australia. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://wilddogplan.org.au/media_release/time-to-reinstate-the-dingo-unprotection-order-in-northwest-victoria/#:~:text=Last%20week%20the%20Australasian%20Mammal,basis%20for%20the%20Victorian%20Government’s

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [online], (no date). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. [Viewed 13 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.iucnredlist.org/

- Conservation (date unknown) Dingo Den Animal Rescue. Available at: https://www.dingoden.net/conservation.html#:~:text=Even%20though%20the%20Dingo%20is,National%20Parks%20and%20Wildlife%20Act (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- National parks and wildlife act 1974 no 80 (date unknown) New South Wales – Parliamentary Councel’s Office. Available at: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1974-080 (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Rural Lands Protection Act 1998 no 143 (date unknown) New South Wales – Parliamentary Councel’s Office. Available at: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/2009-04-07/act-1998-143#:~:text=An%20Act%20to%20provide%20for,and%20for%20the%20functions%20of (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Cairns, D.K. (2024) Why is this Australian icon being poisoned, trapped and shot?, Animals Australia. Available at: https://animalsaustralia.org/our-work/wildlife/dingoes/ (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Fisheries, A. and (2024) Wild dog control and the law, Business Queensland. Available at: https://www.business.qld.gov.au/industries/farms-fishing-forestry/agriculture/biosecurity/animals/invasive/wild-dogs/law (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Wild dogs in Western Australia (date unknown) Agriculture and Food. Available at: https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/state-barrier-fence/wild-dogs (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Department of Primary Industries and Regions (date unknown) Declared animal policy: Wild dogs and dingoes. Available at: https://pir.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/388159/declared-animal-policy-wild-dog.pdf (Accessed: 05 August 2024).

- Cairns, K.M., Crowther, M.S., Parker, H.G., Ostrander, E.A. and Letnic, M., 2023. Genome‐wide variant analyses reveal new patterns of admixture and population structure in Australian dingoes. Molecular Ecology, 32(15), pp.4133-4150.

- Vic.gov.au. (2024). Dingo protection in north-west Victoria. [online] Available at: https://www.vic.gov.au/dingo-protection-north-west-victoria?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTAAAR2BzxmyAW1nRaOOk2X07QetcTORvpxHyyw6IbmR7RaiqPXZa_Uw854tglY_aem_F9hT7cGqZjIuqTF08y16pA [Accessed 17 Aug. 2024].

- BGLC. (2023). Protecting Wilkerr | BGLC. [online] Available at: https://www.bglc.com.au/general-5 [Accessed 17 Aug. 2024].